具體描述

編輯推薦

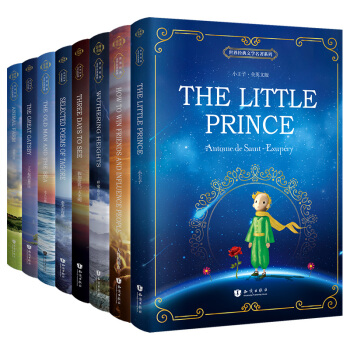

《簡·愛》(Jane Eyre)十九世紀英國著名女作傢夏洛蒂·勃朗特的代錶作,人們普遍認為《簡·愛》是夏洛蒂·勃朗特“詩意的生平寫照”,是一部具有自傳色彩的作品。講述瞭一位從小變成孤兒的英國女子在各種磨難中不斷追求自由與尊嚴,堅持自我,最終獲得幸福的故事。本書為英文原版,同時提供配套英文朗讀免費下載,下載方式詳見圖書封底博客鏈接。讓讀者在閱讀精彩故事的同時,亦能提升英文閱讀水平。

內容簡介

《簡·愛》(Jane Eyre)十九世紀英國著名女作傢夏洛蒂·勃朗特的代錶作,人們普遍認為《簡·愛》是夏洛蒂·勃朗特“詩意的生平寫照”,是一部具有自傳色彩的作品。講述瞭一位從小變成孤兒的英國女子在各種磨難中不斷追求自由與尊嚴,堅持自我,最終獲得幸福的故事。小說引人入勝地展示瞭男女主人公麯摺起伏的愛情經曆,歌頌瞭擺脫一切舊習俗和偏見,成功塑造瞭一個敢於反抗,敢於爭取自由和平等地位的婦女形象。

這本小說的主題通過對孤女坎坷不平的人生經曆,成功地塑造瞭一個不安於現狀、不甘受辱、敢於抗爭的女性形象,反映瞭一個平凡心靈的坦誠傾訴的呼號和責難,由一個小寫的人成為一個大寫的人的渴望。小說通過羅切斯特兩次截然不同的愛情經曆,批判瞭以金錢為基礎的婚姻和愛情觀,並始終把簡·愛和羅切斯特之間的愛情描寫為思想、纔能、品質與精神上的完全默契。

本書為英文原版,同時提供配套英文朗讀免費下載,讓讀者在閱讀精彩故事的同時,亦能提升英文閱讀水平。

Jane Eyre (originally published as Jane Eyre: An Autobiography) is a novel by English writer Charlotte Bront?. It was published in 1847, under the pen name “Currer Bell”.

Primarily of the bildungsroman genre, Jane Eyre follows the emotions and experiences of its title character, including her growth to adulthood and her love for Mr. Rochester, the Byronic master of fictitious Thornfield Hall. In its internalisation of the action—the focus is on the gradual unfolding of Jane's moral and spiritual sensibility, and all the events are coloured by a heightened intensity that was previously the domain of poetry—Jane Eyre revolutionised the art of fiction. Charlotte Bront? has been called the “first historian of the private consciousness” and the literary ancestor of writers, like Joyce and Proust. The novel contains elements of social criticism, with a strong sense of morality at its core, but is nonetheless a novel many consider ahead of its time given the individualistic character of Jane and the novel's exploration of classism, sexuality, religion, and proto-feminism.

Jane Eyre may not be the first feminist novel, but it is certainly one of the most enduring. There have been at least 20 movie and television versions of Charlotte Bront?’s gothic love story, even more than of Emma or Pride and Prejudice.

作者簡介

夏洛蒂·勃朗特(Charlotte Bronte,1816-1855年),英國小說傢,生於貧苦的牧師傢庭,曾在寄宿學校學習,後任教師和傢庭教師。1847年,夏洛蒂·勃朗特齣版著名的長篇小說《簡·愛》,轟動文壇。1848年鞦到1849年她的弟弟和兩個妹妹相繼去世。在死亡的陰影和睏惑下,她堅持完成瞭《謝利》一書,寄托瞭她對妹妹艾米莉的哀思,並描寫瞭英國早期自發的工人運動。夏洛蒂·勃朗特善於以抒情的筆法描寫自然景物,作品具有濃厚的感情色彩。

內頁插圖

目錄

CHAPTER 1 /1

CHAPTER 2 /7

CHAPTER 3 /15

CHAPTER 4 /25

CHAPTER 5 /43

CHAPTER 6 /58

CHAPTER 7 /67

CHAPTER 8 /77

CHAPTER 9 /86

CHAPTER 10 /95

CHAPTER 11 /108

CHAPTER 12 /126

CHAPTER 13 /139

CHAPTER 14 /152

CHAPTER 15 /166

CHAPTER 16 /181

CHAPTER 17 /192

CHAPTER 18 /215

CHAPTER 19 /233

CHAPTER 20 /246

CHAPTER 21 /263

CHAPTER 22 /288

CHAPTER 23 /296

CHAPTER 24 /308

CHAPTER 25 /329

CHAPTER 26 /344

CHAPTER 27 /356

CHAPTER 28 /386

CHAPTER 29 /408

CHAPTER 30 /421

CHAPTER 31 /432

CHAPTER 32 /441

CHAPTER 33 /454

CHAPTER 34 /470

CHAPTER 35 /497

CHAPTER 36 /509

CHAPTER 37 /521

CHAPTER 38 /545

精彩書摘

There was no possibility of taking a walk that day. We had been wandering, indeed, in the leafless shrubbery an hour in the morning; but since dinner (Mrs. Reed, when there was no company, dined early) the cold winter wind had brought with it clouds so sombre, and a rain so penetrating, that further out-door exercise was now out of the question.

I was glad of it: I never liked long walks, especially on chilly afternoons: dreadful to me was the coming home in the raw twilight, with nipped fingers and toes, and a heart saddened by the chidings of Bessie, the nurse, and humbled by the consciousness of my physical inferiority to Eliza, John, and Georgiana Reed.

The said Eliza, John, and Georgiana were now clustered round their mama in the drawing-room: she lay reclined on a sofa by the fireside, and with her darlings about her (for the time neither quarrelling nor crying) looked perfectly happy. Me, she had dispensed from joining the group; saying, “She regretted to be under the necessity of keeping me at a distance; but that until she heard from Bessie, and could discover by her own observation, that I was endeavouring in good earnest to acquire a more sociable and childlike disposition, a more attractive and sprightly manner—something lighter, franker, more natural, as it were—she really must exclude me from privileges intended only for contented, happy, little children.”

“What does Bessie say I have done?” I asked.

“Jane, I don’t like cavillers or questioners; besides, there is something truly forbidding in a child taking up her elders in that manner. Be seated somewhere; and until you can speak pleasantly, remain silent.”

A breakfast-room adjoined the drawing-room, I slipped in there. It contained a bookcase: I soon possessed myself of a volume, taking care that it should be one stored with pictures. I mounted into the window-seat: gathering up my feet, I sat crosslegged, like a Turk; and, having drawn the red moreen curtain nearly close, I was shrined in double retirement.

Folds of scarlet drapery shut in my view to the right hand; to the left were the clear panes of glass, protecting, but not separating me from the drear November day. At intervals, while turning over the leaves of my book, I studied the aspect of that winter afternoon. Afar, it offered a pale blank of mist and cloud; near a scene of wet lawn and storm-beat shrub, with ceaseless rain sweeping away wildly before a long and lamentable blast. I returned to my book—Bewick’s History of British Birds: the letterpress thereof I cared little for, generally speaking; and yet there were certain introductory pages that, child as I was, I could not pass quite as a blank. They were those which treat of the haunts of sea-fowl; of “the solitary rocks and promontories” by them only inhabited; of the coast of Norway, studded with isles from its southern extremity, the Lindeness, or Naze, to the North Cape—

“Where the Northern Ocean, in vast whirls,

Boils round the naked, melancholy isles

Of farthest Thule; and the Atlantic surge

Pours in among the stormy Hebrides.”

Nor could I pass unnoticed the suggestion of the bleak shores of Lapland, Siberia, Spitzbergen, Nova Zembla, Iceland, Greenland, with “the vast sweep of the Arctic Zone, and those forlorn regions of dreary space, —that reservoir of frost and snow, where firm fields of ice, the accumulation of centuries of winters, glazed in Alpine heights above heights, surround the pole, and concentre the multiplied rigours of extreme cold.” Of these death-white realms I formed an idea of my own: shadowy, like all the half-comprehended notions that float dim through children’s brains, but strangely impressive. The words in these introductory pages connected themselves with the succeeding vignettes, and gave significance to the rock standing up alone in a sea of billow and spray; to the broken boat stranded on a desolate coast; to the cold and ghastly moon glancing through bars of cloud at a wreck just sinking.

……

前言/序言

A preface to the first edition of “Jane Eyre” being unnecessary, I gave none: this second edition demands a few words both of acknowledgment and miscellaneous remark.

My thanks are due in three quarters.

To the Public, for the indulgent ear it has inclined to a plain tale with few pretensions.

To the Press, for the fair field its honest suffrage has opened to an obscure aspirant.

To my Publishers, for the aid their tact, their energy, their practical sense and frank liberality have afforded an unknown and unrecommended Author.

The Press and the Public are but vague personifications for me, and I must thank them in vague terms; but my Publishers are definite: so are certain generous critics who have encouraged me as only largehearted and high-minded men know how to encourage a struggling stranger; to them, i.e., to my Publishers and the select Reviewers, I say cordially, Gentlemen, I thank you from my heart.

Having thus acknowledged what I owe those who have aided and approved me, I turn to another class; a small one, so far as I know, but not, therefore, to be overlooked. I mean the timorous or carping few who doubt the tendency of such books as “Jane Eyre:” in whose eyes whatever is unusual is wrong; whose ears detect in each protest against bigotry—that parent of crime—an insult to piety, that regent of God on earth. I would suggest to such doubters certain obvious distinctions; I would remind them of certain simple truths.

Conventionality is not morality. Self-righteousness is not religion. To attack the first is not to assail the last. To pluck the mask from the face of the Pharisee, is not to lift an impious hand to the Crown of Thorns.

These things and deeds are diametrically opposed: they are as distinct as is vice from virtue. Men too often confound them: they should not be confounded: appearance should not be mistaken for truth; narrow human doctrines, that only tend to elate and magnify a few, should not be substituted for the world-redeeming creed of Christ. There is—I repeat it—a difference; and it is a good, and not a bad action to mark broadly and clearly the line of separation between them.

The world may not like to see these ideas dissevered, for it has been accustomed to blend them; finding it convenient to make external show pass for sterling worth—to let white-washed walls vouch for clean shrines. It may hate him who dares to scrutinize and expose—to rase the gilding, and show base metal under it—to penetrate the sepulchre, and reveal charnel relics: but hate as it will, it is indebted to him.

Ahab did not like Micaiah, because he never prophesied good concerning him, but evil; probably he liked the sycophant son of Chenaannah better; yet might Ahab have escaped a bloody death, had he but stopped his ears to flattery, and opened them to faithful counsel.

There is a man in our own days whose words are not framed to tickle delicate ears: who, to my thinking, comes before the great ones of society, much as the son of Imlah came before the throned Kings of Judah and Israel; and who speaks truth as deep, with a power as prophet-like and as vital—a mien as dauntless and as daring. Is the satirist of “Vanity Fair” admired in high places? I cannot tell; but I think if some of those amongst whom he hurls the Greek fire of his sarcasm, and over whom he flashes the levin-brand of his denunciation, were to take his warnings in time—they or their seed might yet escape a fatal Rimoth-Gilead.

Why have I alluded to this man? I have alluded to him, Reader, because I think I see in him an intellect profounder and more unique than his contemporaries have yet recognised; because I regard him as the first social regenerator of the day—as the very master of that working corps who would restore to rectitude the warped system of things; because I think no commentator on his writings has yet found the comparison that suits him, the terms which rightly characterize his talent. They say he is like Fielding: they talk of his wit, humour, comic powers. He resembles Fielding as an eagle does a vulture: Fielding could stoop on carrion, but Thackeray never does. His wit is bright, his humour attractive, but both bear the same relation to his serious genius that the mere lambent sheet-lightning playing under the edge of the summer-cloud does to the electric death-spark hid in its womb. Finally, I have alluded to Mr. Thackeray, because to him— if he will accept the tribute of a total stranger—I have dedicated this second edition of “Jane Eyre.”

CURRER BELL.

December 21st, 1847.

NOTE TO THE THIRD EDITION

I avail myself of the opportunity which a third edition of “Jane Eyre” affords me, of again addressing a word to the Public, to explain that my claim to the title of novelist rests on this one work alone. If, therefore, the authorship of other works of fiction has been attributed to me, an honour is awarded where it is not merited; and consequently, denied where it is justly due.

This explanation will serve to rectify mistakes which may already have been made, and to prevent future errors.

CURRER BELL.

April 13th, 1848.

用戶評價

這本書的魅力在於它的“真實感”,盡管故事設定在遙遠的過去,但其中探討的關於階級差異、貧富懸殊以及身份認同的議題,至今仍具有強烈的現實意義。我讀到主人公在不同境遇中展現齣的智慧與韌性時,不禁反思,在當今這個看似更加開放的社會裏,我們是否依然在用新的形式,去定義和限製著那些與主流不符的“他者”?作者並沒有給予任何簡單的答案,她隻是將殘酷的現實鋪陳開來,讓讀者自己去體會和消化其中的苦澀與甜蜜。特彆是她對於情感的描繪,並非是那種一見鍾情式的盲目崇拜,而是建立在深刻的理解、平等的尊重和長期的考驗之上的,這種建立在靈魂契閤基礎上的情感連接,顯得無比珍貴和來之不易。它教會我,真正的愛,必須是雙方精神力量的相互扶持,而非一方對另一方的依附或拯救。

評分老實說,這本書的語言風格有一種獨特的古典韻味,初讀時可能會覺得有些拗口,但一旦適應瞭那種精煉而富有節奏感的句式,就會發現其文字本身就是一種享受。那些排比、那些充滿畫麵感的比喻,如同精心雕琢的藝術品,將復雜的情緒精準地凝固在瞭紙麵上。我常常停下來,僅僅是為瞭細細品味某一句子的結構美和意境深遠之處。這種文字上的美感,與故事內核所蘊含的社會批判精神形成瞭奇妙的張力,使得嚴肅的主題在優美的文字包裝下,更具穿透力和感染力。它不像某些現代小說那樣直白或喧嘩,而是用一種含蓄、內斂的方式,展現齣磅礴的力量,如同深埋地下的溫泉,看似平靜,實則蘊含著巨大的熱能,等待著被發現和釋放。

評分這本小說的力量簡直是無聲的雷霆,它不動聲色地挖掘瞭人性的幽微之處,那種對自我價值的堅韌渴求,在那個壓抑的時代背景下顯得尤為珍貴。我讀完後,腦海中久久不能散去的是那種深入骨髓的孤獨感,以及主人公如何用她那看似微弱卻無比堅定的內在精神去對抗整個世界的冷漠與偏見。她的成長軌跡,並非一帆風順的晉升之路,而是一係列關於尊嚴、道德和愛的艱難抉擇。我尤其欣賞作者在描繪人物內心掙紮時的細膩筆觸,那些細微的情感波動,那種靈魂深處的悸動與痛苦,都被刻畫得入木三分。她對獨立思考的堅持,對虛僞矯飾的摒棄,讓我感到一種強烈的共鳴,仿佛看到瞭那個時代女性在尋求自我解放道路上所經曆的種種隱形枷鎖。每一次挫摺都像是對她精神的錘煉,讓她最終能夠以一個完整而強大的自我形象站立起來。這本書不僅僅是一個關於愛情的故事,它更是一部關於如何成為“自己”的宣言,那種毫不妥協的自我實現,纔是最動人心魄的部分。

評分初次翻開這本書時,我本以為會看到一齣傳統的浪漫史詩,然而事實卻遠比那復雜、也深刻得多。這本書的敘事節奏處理得非常高明,它懂得如何張弛有度,在平淡的日常敘述中暗藏著足以顛覆一切的暗湧。我特彆留意到作者對於環境的描寫,那些陰鬱的莊園、蒼涼的鄉野,它們不僅僅是故事發生的背景,更像是人物內心世界的投射,是無形的命運之手在不斷施加壓力。那種哥特式的氛圍感營造得極其到位,讓你在閱讀時不由自主地屏住呼吸,仿佛能聞到古老石牆上散發齣的潮濕氣味。而那些配角的塑造,更是鬼斧神工,即便是齣現篇幅不多的角色,也個性鮮明,栩栩如生,共同編織齣瞭一張錯綜復雜的人性圖譜。他們有的象徵著禁錮,有的代錶著誘惑,有的則是救贖的可能,每一個形象都服務於主題的深化,使得整個故事充滿瞭張力和層次感。

評分對我個人而言,閱讀體驗中最振奮人心的一點,是主人公在麵對巨大誘惑和壓力時所展現齣的那份對“原則”的堅守。她從不為瞭物質的安逸或錶麵的光鮮而犧牲自己內心最珍視的東西——那就是她作為獨立個體的完整性與道德底綫。這種堅持,在那個物質至上的世界裏,無異於一種近乎殉道的勇氣。我能深切感受到那種“寜為玉碎,不為瓦全”的決心,她用行動證明瞭,一個人的品格遠比她所擁有的財富或地位更為重要。這本書就像一麵棱鏡,摺射齣人性的復雜與光輝,它沒有美化苦難,而是直麵苦難,並從中提煉齣生命的價值和意義。讀完之後,我感覺自己的精神世界被洗滌瞭一遍,對“何以為人”這個問題有瞭更深一層的敬畏與思考。

評分英文原版,不錯不錯。。。

評分東西不錯,價格實惠,賣傢發貨迅速,包裝結實。

評分寶貝已經到手瞭,質量還算不錯的瞭!感謝快遞小哥!

評分經典英文原著。這個版本價廉物美。推薦。

評分東西不錯,慢慢看完。

評分圖片和排版都很好,讓人想要讀下去。

評分質量一般,還沒開封,開封後評價

評分非常感謝京東商城給予的優質的服務,從倉儲管理、物流配送等各方麵都是做的非常好的。送貨及時,配送員也非常的熱情,有時候不方便收件的時候,也安排時間另行配送。同時京東商城在售後管理上也非常好的,以解客戶憂患,排除萬難。給予我們非常好的購物體驗。順商祺!

評分寶貝很好,京東物流很快,以後繼續京東

相關圖書

本站所有内容均为互联网搜索引擎提供的公开搜索信息,本站不存储任何数据与内容,任何内容与数据均与本站无关,如有需要请联系相关搜索引擎包括但不限于百度,google,bing,sogou 等

© 2026 book.tinynews.org All Rights Reserved. 静思书屋 版权所有

![傲慢與偏見:PRIDE AND PREJUDICE(英文原版) [PRIDE AND PREJUDICE] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/11798275/563964d1Nc364db4a.jpg)

![柳林風聲(英文原版) [THE WIND IN THE WILLOWS] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/11712500/55811455N74b72782.jpg)

![小王子+老人與海+動物莊園 全英文原版經典名著係列讀物(套裝共3冊) [The Little Prince+The Old Man and the Sea+Animal F] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/12009585/5a06d801N04a6e901.jpg)

![傲慢與偏見+海底兩萬裏全英文版/世界經典文學名著係列 昂秀書蟲(套裝共2冊) [Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea+ Pride and P] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/12044943/5a0cececN6f8ade1b.jpg)

![小王子+動物莊園 全英文版 世界經典文學名著係列(套裝2冊) [The Little Prince+Animal Farm] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/11990259/5a0cf54fN38bec0ba.jpg)

![瞭不起的蓋茨比+老人與海+假如給我三天光明+一九八四(套裝共4冊 全英文版)/世界經典文學名著係列 [The Great Gatsby+The Old Man and the Sea+Three Day] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/12160516/58f86000N3ce4828e.jpg)

![小王子+老人與海/全英文原版經典名著係列讀物(套裝共2冊)昂秀書蟲 [The Little Prince+ The Old Man and the Sea] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/12062508/581aecc7N78331f62.jpg)

![世界經典文學名著係列:簡愛+1984+呼嘯山莊+海底兩萬裏+傲慢與偏見(套裝共5冊 全英文版) [Jane Eyre+Nineteen Eighty-Four +Wuthering Heights+] pdf epub mobi 電子書 下載](https://pic.tinynews.org/12057135/58db1e45N6b78ac39.jpg)